The Cannabis Industry & Game Theory

Why would a for profit company purposefully sell at a lost and much more

Here’s a question in regards to rescheduling and the lifting of 280E:

Will the windfall of retained earnings be used to lower SKU costs in a price undercutting attempt to gain market share or will the companies in large part happily retain the money and deploy that to such things as debt pay down, stock buybacks, Capex etc?

What triggered this article were the following woefully simplistic answers in regards to the above question.

“The price in a market is determined by what the market can bear”

“Overall, I think prices will be a function of demand and supply.”

Those quotes aren’t a refutation towards the topic at hand, which is in regards to what companies will do with the proceeds they receive from the removal of 280E.

The quote is yet again, another true statement that is logically valid.

Remember folks,

The logical validity of an argument is a function of its internal consistency, not the truth value of its premises.

The insidious thing about these sorts of statements like the quotes above, is that they’re technically true but incomplete and thus inaccurate in reflecting reality. Which means you’ll be inaccurate in your investing. The problem is that it’s not true enough to provide a comprehensive understanding of price determination or to capture the full range of factors that influence prices in a market. It also leaves a lot to the imagination as to how specific players will position themselves. Simply put, there’s a lot of moving parts.

This often leads people to make false conclusions as a consequence of a partial premise that didn’t factor in a fuller spectrum of variables. Ultimately, this leads to a mismatch between expectations and reality due to not modeling the world accurately. And that doesn’t sound like a strategy for living a quality life. What he did was provide a thesis and jump to conclusions. What he failed to incorporate was the antithesis and synthesis. I covered that in this article under the segment thesis, antithesis & synthesis.

“Why would a for profit company lower its prices?” Or, “Why would a for profit company sell its SKUs at a loss?”

Let's try to answer those questions.

GAME THEORY

Let's take a quick overview of some common terms we’ve all heard before but within the context of the cannabis industry. Then we’ll jump into the Bertrand, Cournot and Stackelberg models of competition. Then I’ll wrap things up with some closing thoughts.

Price gouging:

This was the early days of cannabis.

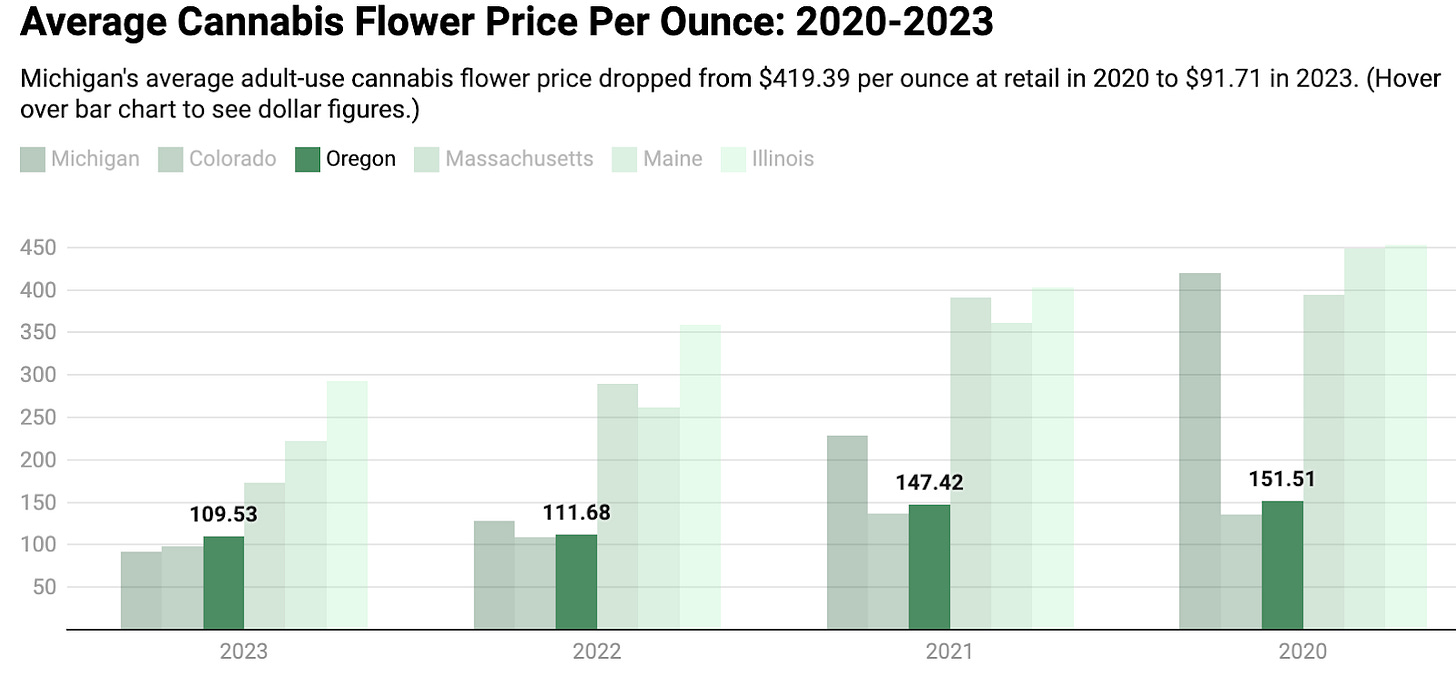

Companies were selling at prices that weren’t sustainable due to the supply-demand imbalance. The sudden shock of demand coupled with lead times of growing facilities created a lag dynamic which subsequently and foreseeably led to overabundance and falling prices like the below image.

Companies take advantage of the scarcity by raising prices. Those who can afford it pay while those who can’t get priced out. It doesn’t matter if it’s water bottles after a natural disaster, beanie babies or oil price shocks from embargos. This is often how the game is played regardless of your moral objections to it.

Distressed pricing:

This is where we’ve been for roughly the last year or so.

Companies have been selling below the cost of production.

This happens within the context of excess supply. It’s where there’s a surplus and glut of inventory.

It’s also the logical consequence of an emerging growth industry that’s heavily fragmented due to how operators often defect from cooperation to gain a first mover advantage in order to make unsustainable profits and gain market share.

This could be considered a right-sizing period. The collective group of companies put too much supply on the market and are now trying to curtail production while selling off inventory. The reason that companies are willing to sell at below their cost of production is in order to retain their customer base. They’re merely hoping to recoup as much money as possible. At this point they’re essentially subsidizing the customers in the interim until the supply on an industrial wide level gets worked through and future output is more balanced with the demands of the market.

Distressed pricing is often seen as a short-term strategy. Distressed pricing looks similar to predatory pricing. With the main difference being that it’s not aimed at driving competitors out of the market or gaining long-term market power. If that happens then it’s a happy coincidence but the focus is about short-term survival.

Predatory Pricing:

Is where things might be heading.

Predatory pricing refers to a strategy where a company sells a product for cheaper than what it costs them to make it or below the prevailing market prices in order to drive competitors out of the market and deter potential entrants. This is a way that price wars can happen and margins get squeezed. Once the competition backs down or is driven out of the market entirely the predatory pricer will subsequently raise prices to recoup their losses. This is how market leaders are established, in part.

Predatory pricing isn’t just about selling weed cheaper than other market participants. For instance, a mechanism of predatory pricing is loss leading.

Loss leading occurs when a company intentionally sells a product or service at a loss with the goal of attracting customers and gaining a competitive advantage via market share. The idea is to lure customers in with the low-priced products and then generate additional sales or profits from related or complementary products.The strategy behind loss leading is that while the company may incur losses on the initial product, it expects to make up for those losses through the sale of other products or services. By using the loss leader to attract customers, the company aims to increase overall sales volume and capture a larger market share, which can lead to long-term profitability.

It’s important to know that the above 3 pricing strategies play out differently in different competition models and settings. Meaning that they shouldn’t be viewed only in isolation and in a false absolute sense because in all reality they’re context dependent.

Now onto a few different competition models that might best describe the cannabis sector. I’ll name them sequentially as to where we were, where we’re at and where we’re going. This is also the form that many new industries take so there’s historical precedence to support this. This is the successive sequence of growth that seemingly is an intrinsic and immutable phenomenon since time immemorial for new emerging industries. I touched upon this topic in the Arc of Development of New Industry segment of an article I’ve written.

Bertrand Competition: This model is where we were. This strategic model predominantly focuses on pricing. As far as an individual participant is concerned the sky's the limit on quantity. Oftentimes the logical outcome of this is that the collective group of players oversaturate and oversupply the market. In the cannabis industry, Bertrand competition would involve multiple producers or dispensaries independently setting prices for their products. Each company's primary objective is to attract customers by offering lower prices compared to competitors. This model assumes that customers will choose the product with the lowest price, leading to price undercutting and intense competition among cannabis businesses.

This is the stage that CEOs will lie to you saying that they’re all about the customer and that’s why they have the best prices. Symptomatically it appears that way but there’s other factors also driving their behavior. I touched upon that in a recent article I’ve written. The C-Suites know that the average person doesn’t know about the market forces at play so they don’t speak about them and instead refocuses the consumers attention to falsely attributed farce and fairytale causes as to what’s going on for grandstanding and pseudo virtue signaling purposes. This happens because they want their brand to resonate with consumers as a consequence of their product not being that differentiated from others, the customers not being able to distinguish between products or as a consequence of their customers not having the acquired skills or care to differentiate. At the end of the day a lot of people just want the best bang for their buck.

Price and THC were the #3 & #4 considerations for consumers based upon this study. And I would imagine that many people would be willing to compromise on quality and strain when something of similar quality is cheaper…thus the predatory pricing dynamic.

Cournot Competition: this stage lines up well with the distressed pricing period we outlined earlier. This is where we’re at in the cannabis industry but are still suffering a hangover from the Bertrand competition phase. Cournot competition in the cannabis industry would involve companies determining the quantity of cannabis they will produce and supply to the market. Each independent player starts taking into account the expected production decisions of other companies. The total quantity supplied in the market determines the market price. In this model, the companies strategically choose their production levels to maximize their market share and profits. Two key distinctions that make this different from the Bertrand stage.

This focuses more on the quantity of product than the price of the product. This is done out of necessity. It’s often a consequence of them oversupplying the market. As though it wasn’t foreseeable 🙄(that’s how they’ll depict it in order to maintain plausible deniability or not to appear grossly negligent). But in all fairness it’s not like they had many options due to perverse incentives and such.

Most importantly, this model reveals that independent players start taking into consideration what other market participants are doing. In Prisoners Dilemma lingo the market participants went from defecting to now loosely “cooperating”. They start recognizing that their outcome and degree of success is to some extent dependent on what others do. They start thinking about their actions in the context of others actions.

Stackelberg Competition: In the cannabis industry, Stackelberg competition would occur when there is a dominant player or leader and other companies act as followers. The leading company, such as a large established producer, sets its pricing or production level first. The follower companies observe the leader's actions and respond accordingly. The leader's advantage lies in being able to shape the market and influence the actions of the other companies. There’s a book that touches on this topic called The Myth of Capitalism. The followers' behavior could be thought of as tacit collusion.

So there you have it. They went from thinking selfishly, to factoring in other people's decisions and how that impacts them to ultimately realizing their probable potential and thus cooperating and colluding in a cartel-oligopoly fashion. They grow up so fast, don’t they? The last five years have been them trying to vie for dominance and establish a pecking order. Figures I’ve read suggest that the top 5-6 MSOs only account for roughly 20% of overall revenue in the cannabis industry. If that is true then I’d certainly say that we’re not at a concentrated enough point for Stackelberg to be a concern.

These companies are still trying to find a balance between cooperation and competition.

A reason that we haven’t seen the Stackelberg situation arise yet is because no one is ok with taking second place yet. And the self selection that occurs when CEOs are selected for oftentimes means that these sorts of people aren’t ok with a successful position albeit a lower status. They’re type A personalities who have worked too hard to give up now. By cooperating they compromise and would have to accept their claim to a lower rung in the hierarchy. The asymmetrical risk reward is to go for broke, sometimes quite literally.

The parallels that you can make between an actual infant and an industry in its infantry stage is interesting. It’s an alarming juxtaposition because although a new industry in its infantry stage it is run by grown-ass adults who’d you think would know better. It’s a model of development and succession that none-the-less helps me better understand what’s going on. Who thought that having a cursory understanding of the Piagetian stages of development would help me better understand the cannabis industry?

I would say we’ve entered the Concrete operational stage or will be entering it soon enough. The Sensorimotor stage was them trying to get a grasp on growing (Glasshouse noted how they’ve tried 4 different mediums to grow in), logistics and learning by trial and error in an attempt to understand their environment. The Preoperational stage is them acting in the world without concern or care for the consequences (that leads to unprofitable M&A or oversupplying the market). The Concrete operational stage will be them realizing the horrid condition of their balance sheets, restructuring their business and acting as though there’s actually a future and what they do today isn’t just tomorrow's problem. The Formal operations will look like rational agents who actually want to make money sustainably (in large part, we’re not there yet). Of course this is a simplistic overview and parallel but I find the parallels to be striking and an aid in conceptualizing matters.

In many commodity markets price is set on the margin. Meaning that small fluctuations in volumes can lead to outsized fluctuations in price. Right now, I’d say that the cannabis market is trying to find that sweet spot between price and volume.

Back to 280E

Some players are well positioned to lower SKU’s in an attempt to gain market share via predatory pricing. They’re spoiled for choice, have optionality and aren’t necessitous. While other players are burning cash and have high interest yielding debt. Why wouldn’t the better positioned player squeeze the weaker one in order to grow their business?

The businesses that have proven a viable and profitable economic business don’t necessarily need to make more money. Less well positioned players do need to make more money or they’ll eventually go bankrupt. By using the 280E proceeds to lower their SKU pricing they can take revenues from their competition. And may I remind you, revenues that still weren’t enough to not eventually go bankrupt or at minimum raise more cash via debt or equity offerings.

And if the weaker player competes on price to maintain market share their margins will get worse and further hinder their ability to pay off the debtors. At which point, the better positioned player can drag it out until the weaker player gets bleed out, acquired, goes bankrupt or tries a different vertical to differentiate their products.

And remember, all the while the company that is applying the heat to their competition will still maintain revenue, margins etc. Matter of fact, they’ll likely gain market share and thus grow their revenues albeit at a thinner margin. I don’t think that the ill informed, short sighted, impulsive and emotional average investor understands these dynamics. At least not well enough to cite it as a reason why it might occur. Instead they’re ideologically possessed under some narrative along the lines of “why can’t we all be friends and get along, we’re in this together.” The degree of delusion you need to be under to even posit something of that sort of sentiment is beyond anything that resonates with me. After all, people don’t mind oligopolies tacitly colluding when it’s done to suppress prices. Lol.

The well positioned operators will give competition an ultimatum. Compete on prices or pay down debt. And I assure you that a company paying down debt with falling revenues, although good for the long-term, will not be rewarded by Mr. Market. So who are these players? Hell if I know.

The statement "the price in a market is determined by what it can bear" does not account for all the pertinent contributing factors that impact pricing decisions. It oversimplifies the complex nature of pricing dynamics by focusing solely on the willingness and ability of buyers to pay. As though competitive dynamics don’t play a critical role and thus shouldn’t be considered.

Understanding the dynamics that I outlined today can lead us to preemptively position ourselves or to allow us to factor in different contingency plans.

The sentiment in this industry is one of learned helplessness. Their motto is, “Fool us 17 times shame on you, fool us 18 times shame on us. As the saying goes:

”Those who know it the best, like it the least because they’ve been hurt the most.”

Last but not Least

If we are in the Cournot stage then predatory pricing is limited. Because they’re more focused on getting the inventory and quantity under control. Also, they’re already selling at a loss or break even so most players won’t be particularly interested in lowering prices even more. However, they might once again become emboldened from the 280E proceeds. If they aren’t interested in another pricing war then we could see a “ceasefire” for the meantime. The problem with this analysis is, among other things, is that it looks at the broader participants.

The fact of the matter is that for those well positioned and profitable it would be a great time to squeeze their competition. The 1st positioned player thinks they can squeeze everyone else but the 9th player thinks they can squeeze the 10th positioned player and so on. So will a ceasefire happen or not? That’s to be determined.

An example of this might be Green Thumb having growing revenue but shrinking margins due to Pac-Manning market share. The revenue growth will be the consequence of them gaining market share (where it’s possible) but their margins will shrink due to them undercutting the competition.

If we understand markets then we might be able to identify which market we’re in, that will help us position ourselves in accordance with it and set our expectations. And if markets have a progressive trajectory and successive development to them (which I often believe they do) then we might be able to predict where we're going.

MY CONCERN!

I need to sit down and iron this out but for now here it is.

Most of the people I hear are thinking along these lines.

1 (states begin legalization, decriminalization) →

2 (clear dominant players are established aka MSOs) →

3 (Safer banking, 280E solidifies the dominant MSOs) →

4 (Federal legalization solidifies the MSOs victory)

= The End

Versus what I think might happen.

1 (State legalization, decriminalization) →

2 (Clear dominant players are established aka MSOs) →

3 (Safer banking, 280E, Rescheduling and FDA approval allowing interstate commerce, shakes things up and reconfigures the leaders. The companies that are battle hardened from intense competition of cap-less licensed states who’ve had to compete on quality and cost usurp those who’ve been protected by regulation & barriers to entry and thus were allowed to establish pseudo monopolies.)

OR,

(Along with those legal matters companies get up-listing, capital floods back into the cannabis market and a redux of 2018-2021 happens all over again.) →

4 (Once the dust settles, consolidation happens, prices balance out again, much of the old guard has been replaced or consolidated by forced M&A to survive) →

5 (Federal legalization happens and one last hooray and a 2018-2021 redux occurs with less churn of the dominant players but a heavy consolidation of the industry and a more bifurcated market with less vertically integrated players because why grow the stuff when you can’t compete on price and instead buy wholesale and provide a value added brand) →

6 (The Stackelberg model occurs and cannabis establishes a stable environment with a clear hierarchy of industry leaders) OR a Stackelberg model occurs once new states stop coming online only to be disrupted by Federal legalization at some point in the future. And then one final 2018-2021 redux will occur and it’ll be quite the slow, multi-quarter/year bloodbath.

P.S. none of this even considers Canada's contributions to the American markets and participants.

You see the nonlinear complexity of that? It’s not a pretty picture. And doesn’t bode well to good returns for a long period of time, unless you’re planning to hold for a couple of decades. It’ll also be more difficult to predict the inevitable winners in that. Wild price swings will occur and the market could bounce around within a massive range but ultimately trade sideways for a decade or two. And we haven’t even talked about Canada entering the US market at one of these delineation points.

Anyway, it’s all worth considering and critically evaluating.